In 1824, when Charles Dickens was 12 or 13 years old, his father was arrested for debt and incarcerated in the Marshalsea prison in Southwark. The young Charles was sent out to work in Warren’s Blacking Factory (located in Hungerford Stairs, then Chandos Street) and found himself living alone in lodgings on Little College Street in Camden Town.

In John Forster’s The Life of Charles Dickens (1875), which was based in part on autobiographical fragments given to him by Dickens himself, we read the following description of life at Warren’s:

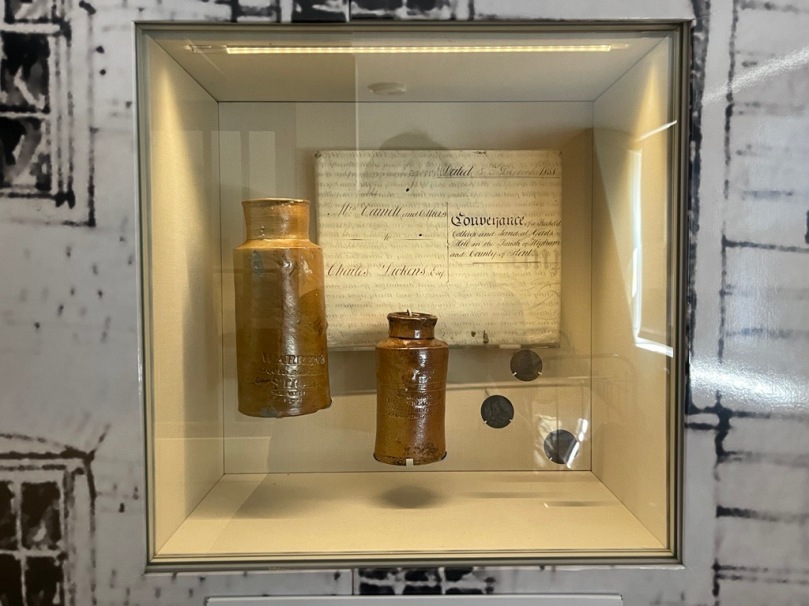

The blacking-warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary’s shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label, and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty down-stairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin; and I took the liberty of using his name, long afterwards, in Oliver Twist.

A few pages later, Forster quotes Dickens again, this time describing his adult responses to the site of his childhood trauma:

Until old Hungerford market was pulled down, until old Hungerford Stairs were destroyed, and the very nature of the ground changed, I never had the courage to go back to the place where my servitude began. I never saw it. I could not endure to go near it. For many years, when I came near to Robert Warren’s in the Strand, I crossed over to the opposite side of the way, to avoid a certain smell of the cement they put upon the blacking-corks, which reminded me of what I was once. It was a very long time before I liked to go up Chandos Street. My old way home by the borough made me cry, after my eldest child could speak.

In my walks at night I have walked there often, since then, and by degrees I have come to write this. It does not seem a tithe of what I might have written, or of what I meant to write.

It is not uncommon for post-traumatic landscapes to be structured by strategies of avoidance – of places, people or activities which trigger memories or thoughts of the traumatic event. Let’s say that someone undergoes a traumatic experience in Berlin. In the first instance, they may simply decide never to return to Berlin and thereby avoid putting themselves in the situation of being confronted with disruptive memories they would rather not have. They may also, however, decide to cut all ties with friends who live in Berlin, for they remind them when they speaks to them of what happened there. They may find it difficult to answer the phone or read their emails, in case they bring news from Berlin. They may become uncomfortable or upset when watching the news on TV and an item about Berlin comes up. If Berlin is in the news, they may decide to no longer watch the TV, listen to the radio or read the newspapers. They will look away from the news stands, their heart racing, in case the front page carries an image or a story that reminds them of the traumatic event, or presents any new information about it. They may be forced to make changes to their professional practice and networks in order to avoid attending conferences and meetings in Berlin, or perhaps meeting colleagues from Berlin in conferences and meetings elsewhere. A newsagent’s decision to stock a German-language newspaper means that a whole detour has to be invented, in order that they do not put themselves in a situation where they might accidentally see a headline that perhaps has a resonance with what happened to them before.

As what happened in Berlin – and Berlin itself – present themselves to them in so many ways, and as their strategies of avoiding anything to do with Berlin proliferate and become more complex, so – to others – their behaviours and responses become more oblique. Avoidance (like trauma, perhaps) is perceived only in the constellation of behaviours and responses that coalesce around it. Sometimes, avoidance behaviours seem so far removed from the original trauma – (why are they refusing to go into the newsagents to buy a coffee from the machine? Why are they making us cross the station to buy a coffee somewhere else, when we’re already running late for our train?) – that they defy understanding, causing others to be irritated, impatient, curious or even angry.

The relief that accompanies the avoidance of trauma reminders is fleeting (though gratifying in the immediate present); each new day threatens the subject with a series of mnemonic and associative dangers. The post-traumatic landscape is constantly and vigilantly re-mapped. As more and more experiences and previously neutral stimuli present themselves as potential dangers, the number of ‘safe routes’ through the landscape is diminished. A space experienced as benign may, due to the spiralling, rhizomic association of perceived dangers, be re-cast as off-bounds. The world becomes significantly smaller.

Dickens felt more able to be near the former site of Warren’s factory only when ‘the very nature of the ground changed’. The transformation to which he refers took place in 1831, following an Act of Parliament that ordered the demolition of the increasingly insalubrious buildings of the Hungerford market area (of which Warren’s was one) and the incorporation of a new company to oversee the site’s redevelopment.

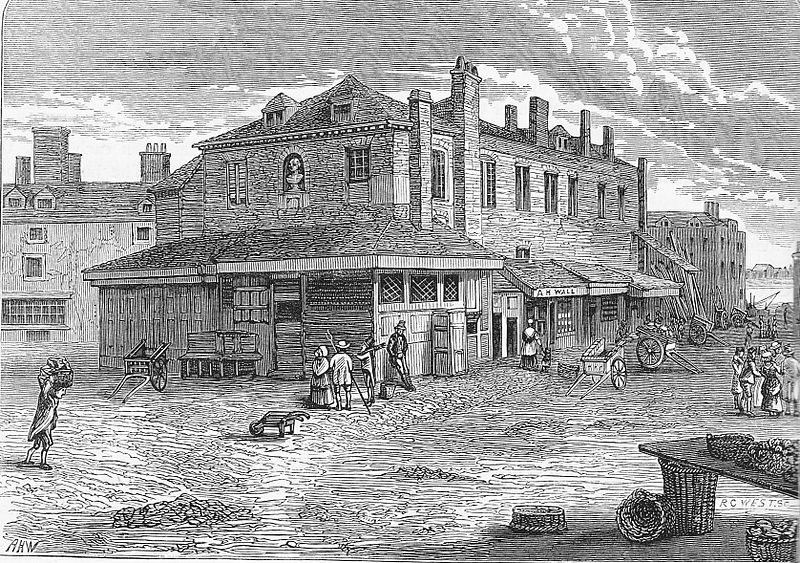

“Old Hungerford Market (from a view published in 1805)”. The bust of Sir Edward Hungerford (d.1711) is visible set into the north wall.

“Old Hungerford Market (from a view published in 1805)”. The bust of Sir Edward Hungerford (d.1711) is visible set into the north wall.Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:OldHungerfordMarket1805.jpg

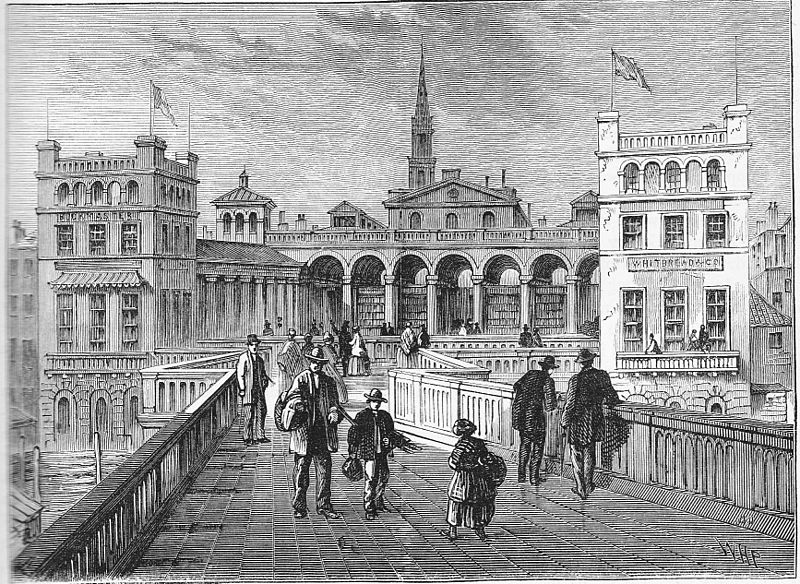

“Hungerford Market, from the bridge, in 1850” (1878)

“Hungerford Market, from the bridge, in 1850” (1878)Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:HungerfordMarket1850.jpg

The new Hungerford market was a dramatic and ornate construction that had little in common architecturally with the site Dickens had known as a twelve year-old child. And yet the site is clearly sticky with its past. The Hungerford name lingered in the area, lending itself to a new hall, a street and a bridge; but perhaps more importantly, the affective resonance of what happened in that place continues to play out. When, as an adult, Dickens finds himself taking the same route he used to take as a child, he experiences involuntary responses that are both embodied and emotional. It is interesting too that the site of trauma bleeds beyond its original spatial containment. Dickens avoids Chandos Street, where Warren’s relocated, because the smells coming from the business’s new premises remind him unbearably of the place where he worked as a child.

Although he mentions the area around Warren’s in his notes to Forster, he barely spoke of this early traumatic experience during his lifetime. His family found it equally difficult to address and articulate what had happened to him: ‘My father and mother had been stricken dumb upon it’ (The National Archives, 2010). Even as the adult Dickens walked those streets, learning, somehow, to absorb the mnemonic shock of the place, he found himself unable to put those place feelings into words. Instead, they play out in a sensory, affective register, the marks of which can be read only obliquely through his scarred spatial practice.