In 2017, I worked alongside Dr Sophie Watt and Dr Casey Strine to create an undergraduate research project, which was funded by the University of Sheffield’s SURE scheme.

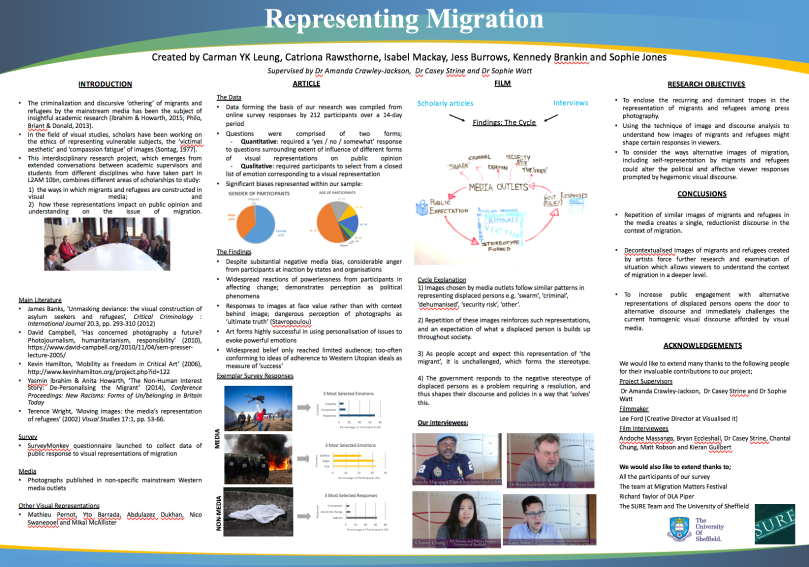

The six second-year undergraduate students worked all summer on the visual representation of refugees in the media:

The research explored how images of migrants and refugees shape public understanding and opinions of migration. Discourses around the threat posed by migrants and refugees to security, order, national identity and integrity have clearly impacted on the contemporary political landscape (for example Brexit, Trump’s election victory and the rise of populism and ethno-nationalism in Europe). As many scholars have observed, the media play a key role in both conveying and legitimising these political messages about migration. Less attention has been paid, however, to the specifically visual representation of displaced peoples and the impact this has on the public perception of migration – a gap this research will seek to address.

The outputs of their research included a 6000-word article, a poster and a film.

In 2016-2017, along with Dr Alastair Buckley from the Department of Physics, I developed a MOOC entitled “10bn”, which offered second-year undergraduate students at the University of Sheffield the opportunity to work together on a variety of wicked problems associated with a predicted global population of 10bn. One of the chapters in the MOOC featured the research project on which I work with Dr Sophie Watt: The Longer Story, The Bigger Picture. It was this work, along with a workshop delivered by Dr Casey Strine on his research about the representation of migration in the Bible, that provided the second-year SURE students with the inspiration for their own research project.

Sophie and I are particularly interested in the ways in which Calais has been represented by artist Mathieu Pernot, in whose images the so-called “jungle” is seen as a post-traumatic landscape from which refugees have been forcefully evacuated. Thus, in Pernot’s work, we see not the refugees themselves, but only a ‘hollow portrait’, a presence in absence made manifest in the scraps and traces they leave behind in the landscape of northern France.

See Mathieu Pernot, Les Migrants (Paris: 2012), translated by Amanda Crawley Jackson;

and Sophie Watt, ‘Voicing the Silence: Exposing French Neo-Colonial History and Practices in Mathieu Pernot’s Les Migrants‘, in Engagement in Twenty First Century French and Francophone Culture, edited by Helena Chadderton and Angela Kimyongür (2017).